Planned obsolescence is a deliberate strategy employed by manufacturers to limit a product’s lifespan or relevance, compelling consumers to purchase replacements or newer models. This strategy is not a product of the modern digital age but has historical roots that trace back to the early 20th century, reflecting a fundamental shift in consumerism and product design philosophy.

The term itself often evokes a range of reactions, from acceptance as a driver of technological innovation to criticism for promoting wasteful consumer habits. Planned obsolescence can be seen in various forms, from physical durability and technical compatibility to trends and fashion. However, its impact goes beyond just encouraging repeat purchases; it touches on environmental concerns, economic models, and social behaviors.

The appearance of planned obsolescence is often linked to the consumer goods explosion in the post-World War II era, where an abundance of products flooded markets, igniting a cycle of buy-use-dispose that has accelerated with technological advancements. This period marked a departure from the principles of durability and repairability that characterized products of the past, ushering in an age where obsolescence became a calculated component of product design and marketing strategies.

However, planned obsolescence is not merely a business strategy; it’s a catalyst for broader discussions about sustainability, consumer rights, and the future of innovation. And it’s crucial we understand its mechanisms, implications, and the role we all play in this cycle of continuous consumption.

How Planned Obsolescence Works

Planned obsolescence mechanisms are multifaceted, working through the lifecycle of a product from its conception to its inevitable decline. Understanding how planned obsolescence functions require a look at this lifecycle, the types of obsolescence employed by manufacturers, and the real-world implications of these practices.

The Lifecycle of a Product: From Launch to Obsolescence

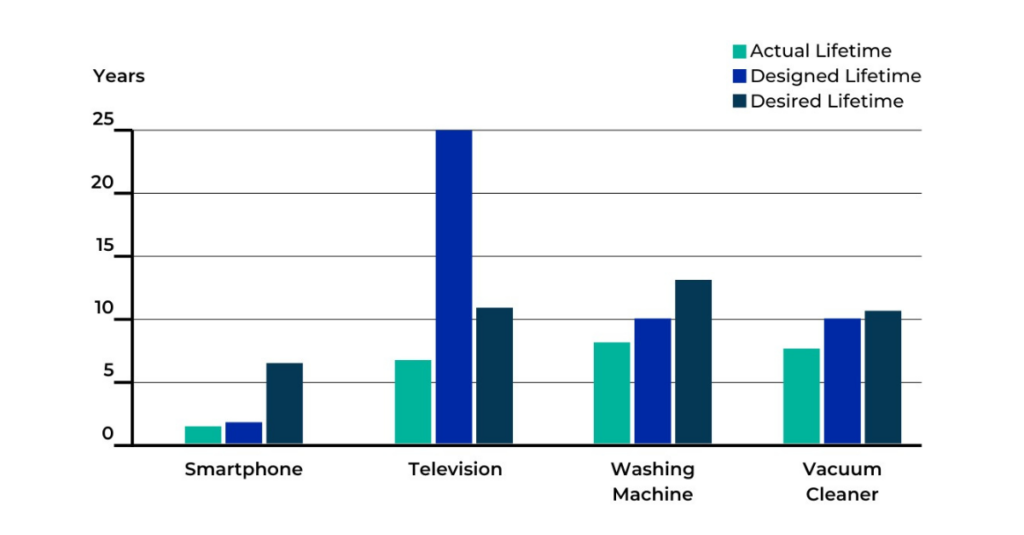

Every product undergoes a lifecycle that begins with its launch into the market, peaks in its popularity and utility, and eventually declines as it becomes obsolete. This journey can be shortened intentionally through planned obsolescence, which is often justified by manufacturers as a means to innovate and improve products. However, the acceleration of this process raises concerns about environmental waste and consumer cost.

Types of Planned Obsolescence

Planned obsolescence has several forms, each with distinct characteristics and outcomes:

-

Technological Obsolescence

Technological advancements make previous models seem inadequate in comparison. Manufacturers may release new versions of a product with features that older models cannot support, effectively making the previous version less desirable or even unusable.

-

Perceived Obsolescence

This type is driven by changes in style, design, or consumer perception, encouraging consumers to purchase new products even when their current ones function perfectly well. It’s prevalent in fashion and electronics, where the latest design prompts consumers to upgrade unnecessarily.

-

Software Obsolescence

Software updates or the lack thereof can render a device less functional or secure. When manufacturers stop providing updates or support for older models, these devices become vulnerable or incompatible with new apps and services.

Case Study: Apple's iPhone and iPad Obsolescence Strategy

A prime example of planned obsolescence in action can be observed in Apple’s approach to its iPhone and iPad lines. For example, the iPhone 6 Plus was introduced in September 2014. It was marked obsolete just a few days ago, seven years after its launch, following Apple’s policy. As well as the iPad mini 4, launched in 2015, that reached “vintage” status after five years since it’s been last sold by Apple, indicating it’s on the path to obsolescence.

Software updates significantly impact the lifecycle of these devices. For instance, iOS 13, released in 2019, did not support the iPhone 6 and 6 Plus, limiting access to new features and security updates for these models. This software cutoff not only affects the usability of older devices but also serves as a nudge for consumers towards newer models.

The Impact of Planned Obsolescence

Waste Generation and Recycling Challenges

One of the most immediate and concerning impacts of planned obsolescence is the increase in electronic waste (e-waste). The rapid turnover of electronic devices, driven by planned obsolescence, contributes significantly to the growing volume of e-waste around the world. According to the United Nations Global E-waste Monitor, the world generated 62 million tonnes of e-waste in 2022 alone. Just to compare, that figure in 2019 was 50 million tonnes. This escalation highlights the urgent need for more sustainable consumption patterns and better recycling technologies.

The challenge with e-waste lies not just in its volume but also in its composition. Electronic devices contain hazardous materials, such as lead, mercury, and cadmium, which pose significant risks to the environment and human health if not properly disposed of or recycled. The recycling process itself is complex and costly, further complicating efforts to mitigate the environmental impact of e-waste.

Consumer Spending Habits

Planned obsolescence also has a direct effect on consumer spending habits. As products become obsolete more quickly, consumers are forced to replace them at a faster rate, leading to increased spending on electronic devices and other goods. This pattern benefits manufacturers and retailers but places a financial burden on consumers, particularly those who cannot afford to continuously purchase new products.

The Debate on Consumer Choice and Freedom

The strategy of planned obsolescence raises important questions about consumer choice and freedom. Critics argue that it limits consumers’ ability to choose more durable and sustainable products, effectively forcing them into a cycle of continuous consumption. This cycle not only has financial implications for consumers but also fosters a throwaway culture that devalues long-lasting products and sustainability.

The debate extends to the right to repair movement, which advocates for legislation to allow consumers more freedom to repair their devices, thus extending their lifespan and combating the effects of planned obsolescence.

Other Big Tech Examples of Planned Obsolescence

While Apple’s practices have often been spotlighted in discussions about planned obsolescence, it is far from the only company to employ such strategies. Across the tech industry, from smartphones to printers and software, planned obsolescence shapes consumer experiences and product lifecycles, influencing both market dynamics and environmental outcomes.

Mobile Phones Industry

In the smartphone sector, companies like Samsung and Huawei also apply planned obsolescence, though their approaches and the public’s reception may vary. Samsung, for example, has faced criticism for the lifespan of its devices, particularly concerning the availability and duration of software updates. While Samsung has made commitments to provide longer support for their devices recently, the historical pattern has contributed to the cycle of upgrading smartphones more frequently than might be necessary.

Huawei, on its part, has contended with additional challenges due to geopolitical tensions that affect its ability to offer Google services on its newer devices. This situation forces a different kind of obsolescence, not entirely planned by Huawei but resulting in a similar effect where consumers feel compelled to replace their devices sooner to maintain access to familiar services and apps.

The Printer Industry

The practices within the printer industry provide a clear example of technological obsolescence. Manufacturers often use software updates or embed chips in printer cartridges to restrict the use of third-party or refilled cartridges, compelling consumers to purchase original and often more expensive replacements. This tactic not only impacts consumer choice and cost but also contributes to environmental waste, as cartridges are disposed of rather than refilled.

The Software Industry

Here, planned obsolescence manifests through forced updates and the discontinuation of support for older versions. Adobe’s shift from perpetual licenses for its Creative Suite to a subscription-based model for Creative Cloud is a notable example. This change effectively made owning a permanent version of Adobe’s software obsolete, as users must now pay a recurring fee to access the latest features and updates.

Similarly, Microsoft has phased out support for older versions of its Windows operating system, pushing users to upgrade to newer versions. While this ensures users have the latest security and performance enhancements, it also means that hardware incompatible with newer versions may be prematurely retired.

These examples across different sectors of the tech industry highlight the pervasive nature of planned obsolescence. While the strategies may vary, the outcome is often the same: shorter product lifecycles, increased consumer spending, and a larger environmental footprint due to the disposal and replacement of devices. As consumers and regulators become more aware of these practices, the demand for more sustainable and transparent approaches to product development and support is likely to grow.

Planned Obsolescence: Tips for Consumers

Understanding how to identify planned obsolescence and employing strategies to extend the lifespan of our electronics can lead to more sustainable consumption habits and significant savings.

How to Identify Planned Obsolescence

Recognizing planned obsolescence involves paying attention to several indicators:

- Short Lifespan: Products that fail soon after warranties expire or software that requires frequent updates can be red flags.

- Non-replaceable Components: Devices with batteries or parts that are difficult or impossible to replace by the user may be designed for a limited lifespan.

- Limited Repair Options: A lack of compatible spare parts or restrictions on who can perform repairs can signal planned obsolescence.

Strategies for Extending the Life of Your Devices

Regular Maintenance Tips

- Physical Care: Protect your devices from physical damage by using cases, screen protectors, and keeping them clean and dust-free.

- Battery Management: Prolong battery life by avoiding extreme temperatures and using manufacturer-recommended chargers.

Software Management

- Update Wisely: While keeping software up to date is crucial for security, be mindful of updates that may overburden older hardware. Check user experiences and reviews before updating.

- Optimize Settings: Disable unnecessary features and apps that consume resources to keep your device running smoothly for longer.

Advocacy and the Right to Repair Movement

The right to repair movement advocates for legislation that would allow consumers more freedom to repair their devices, offering an antidote to some aspects of planned obsolescence. Supporting this movement can involve:

- Educating Yourself and Others: Understand the principles behind the right to repair and discuss them within your community.

- Supporting Legislation: Advocate for and support legislative efforts that promote the right to repair, ensuring manufacturers provide access to parts, tools, and information for repairs.

Globally, consumer advocacy groups and some governments are pushing for laws that counteract planned obsolescence. In the European Union, for example, regulations are being introduced to ensure that appliances can be repaired for up to 10 years after purchase, a significant step towards sustainable consumer electronics.

Rethinking Our Relationship with Technology

In this digital age our relationship with technology has become increasingly complex. The practice of planned obsolescence, while driving innovation, also prompts us to reconsider how we consume and interact with electronic devices. The need for sustainable consumer electronics is more pressing than ever, demanding a collective effort from manufacturers, consumers, and regulators to forge a path towards more responsible technology use.

Sustainability in consumer electronics involves creating products that are designed to last longer, are easier to repair, and have a smaller environmental footprint. It’s about shifting from the current model of rapid obsolescence to one where longevity and repairability are prioritized. This shift not only has the potential to reduce e-waste but also to save consumers money and reduce the demand on raw materials.

The Role of Manufacturers, Consumers, and Regulators

Manufacturers

The responsibility of manufacturers is crucial in addressing planned obsolescence. By designing durable products, offering extended support for software updates, and making repairs more accessible, manufacturers can lead the way in sustainable consumer electronics. Transparency regarding the expected lifespan of products and the availability of repair services can also foster trust and loyalty among consumers.

Consumers

Consumers play a vital role by making informed choices and advocating for their right to repair. Opting for products known for their durability, supporting brands that prioritize sustainability, and engaging in repair and recycling efforts are all ways consumers can help combat planned obsolescence. By voicing their preferences and concerns, consumers can influence the market towards more sustainable practices.

Regulators

Regulators have the authority to implement policies that promote sustainability and protect consumer rights. Legislation that requires manufacturers to provide access to repair manuals, spare parts, and tools can make a significant difference. Initiatives that encourage product designs facilitating easy repairs and longer lifespans can help shift the industry standard.

As we look towards a future where technology and sustainability go hand in hand, it’s clear that a collective effort is needed to address the challenges posed by planned obsolescence. Want to learn more about how you can combat planned obsolescence or need advice on making your devices last longer? Contact WAT for expert guidance and support. Together, we can make informed decisions and promote sustainability in technology. By rethinking our relationship with technology, we can pave the way for a more sustainable and equitable digital future.

FAQ

Q: What is planned obsolescence?

Planned obsolescence is a strategy used by manufacturers to deliberately design or produce products with a limited useful life, so they will become outdated, non-functional, or unfashionable after a certain period. This encourages consumers to purchase new products sooner than they would if the product were made to last longer.

Q: What are examples of planned obsolescence?

Examples of planned obsolescence include smartphones that are no longer supported with software updates after a few years, printers that use chips to limit the number of prints, and fashion trends that change rapidly, making previous styles seem outdated. Another common example is the introduction of new accessory designs that are incompatible with older models of the same product, forcing consumers to buy new versions.

Q: Is planned obsolescence illegal?

Planned obsolescence is not inherently illegal in most countries, but certain practices associated with it can lead to legal issues. For instance, if a company is found to be deliberately making their products fail in order to force consumers to buy replacements, they could face lawsuits or penalties, especially if they mislead consumers about the durability or functionality of their products. Some regions, like the European Union, are implementing regulations to combat practices associated with planned obsolescence by requiring products to be more durable and repairable.

Q: What is an example of planned obsolete?

An example of planned obsolescence is the discontinuation of software updates for older smartphone models. For instance, a smartphone manufacturer may stop providing operating system updates to a model that is several years old, resulting in decreased functionality or security vulnerabilities that compel users to upgrade to a newer model.

Q: Why planned obsolescence is bad?

Planned obsolescence is considered bad for several reasons: it leads to increased environmental waste as products are discarded more frequently; it forces consumers to spend money on new products more often; and it can contribute to a culture of disposability, undermining efforts towards sustainability. Additionally, it can limit consumer choice by making it difficult or expensive to repair products, pushing consumers towards a cycle of constant consumption.

Q: Who invented planned obsolescence?

The concept of planned obsolescence is often linked to Bernard London’s 1932 pamphlet “Ending the Depression Through Planned Obsolescence,” in which he proposed that the government impose a legal obsolescence on consumer articles, to stimulate and perpetuate consumption. However, the practice predates this proposal and has been part of industrial strategies in various forms, with notable adoption by manufacturers in the early to mid-20th century to increase consumer spending and drive economic growth.